The Subversive Sisters of Smith College

Part 1 - The women of Smith College's late Victorian Banjo Club pushed boundaries.

I’m prepping for this year’s Banjo Gathering in Chapel Hill/ Carrboro, North Carolina and I wanted to share a version of the presentation I gave last year. It was longer than expected, so I’ve broken it up into three parts.

As some of you may know, I have a slight crush on Lucy McKim. I first came across her name because she is listed as the third author of the 1867 Slave Songs of the United States, the first published collection of Black American music. I included a bit about Lucy and that collection in Well of Souls: Uncovering the Banjo’s Hidden History, but ultimately most of what I wrote about her got cut.

I was so fascinated by her and the lives of the daughters and sons of prominent abolitionists (including her future husband, the son of William Lloyd Garrison), that I made her one of the main characters of my book A Most Perilous World: The True Story of the Young Abolitionists and Their Crusade Again Slavery, which came out in June.

So in the summer of 2023 while at The Mastheads residency in Pittsfield, I took time to go to Smith College’s archives and view Garrison Family Papers related to Lucy and her brother-in-law George Garrison.

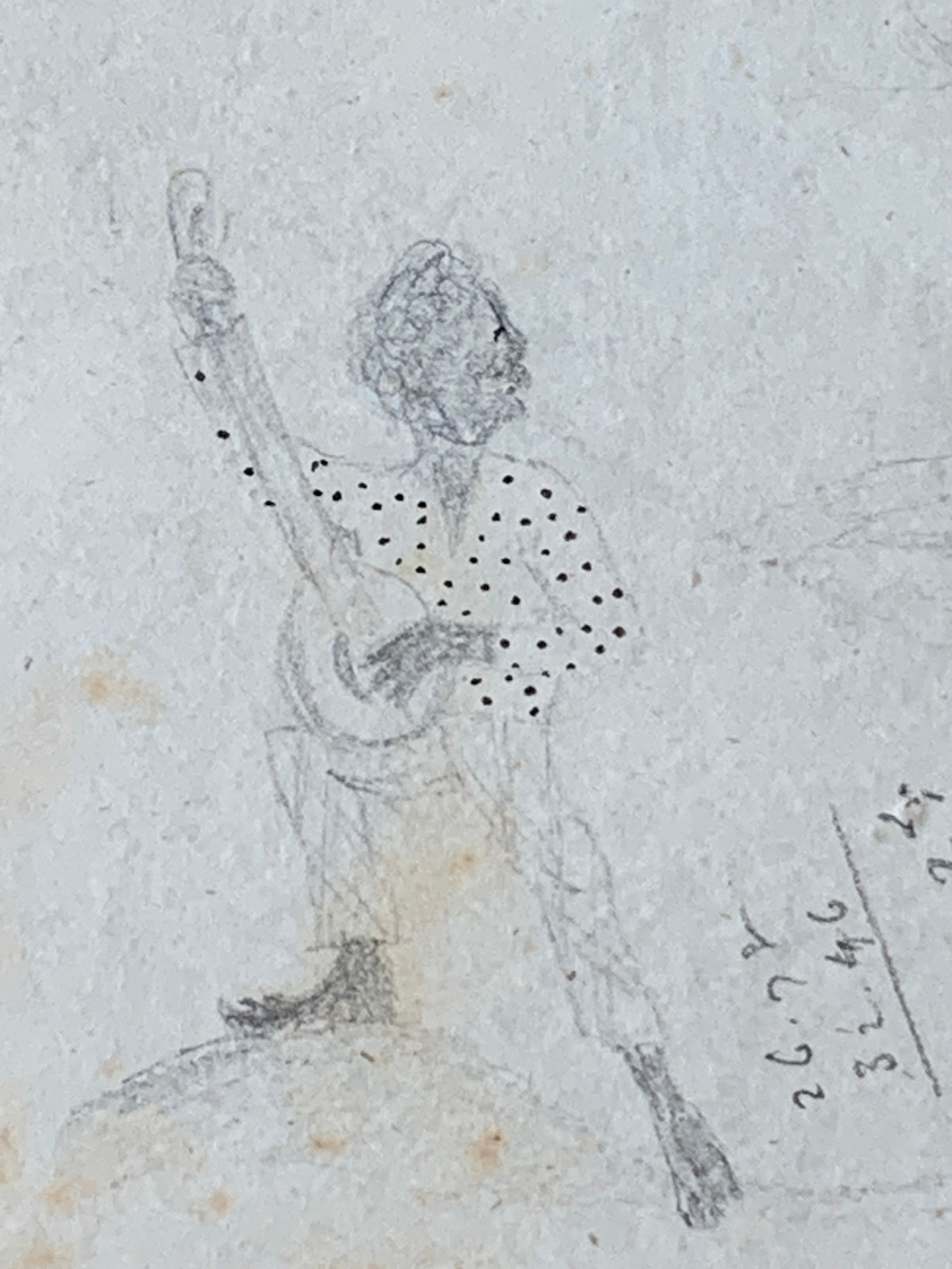

You all might know I’m always looking for banjos–which wouldn’t have been crazy because of the time period of A Most Perilous World (the 1850-60s, when the banjo was becoming widespread with white audiences) and because Lucy’s younger brother played the banjo. So I found this cartoonish sketch done by Lucy’s husband of a black banjo player and references to the Hutchinson Family Singers, also drawn by Wendell Garrison.

Then, I overhead a student employee saying that she’d found a photo of a bluegrass band.

Ok, interesting, I thought, and my ears perked up—she wasn’t talking to me. The student was looking for Halloween photos for a display of archival material they were going to put up. She then kind of corrected herself and said, well, there are banjos, but I don’t know if it is bluegrass.

Even more intriguing. So I walk over and see the image.

We can’t talk about the banjo without talking about America’s history of slavery and reality of racism, and so it was with the photo. It is a group of women, in Blackface with their banjos. They are clearly trying to be a Minstrel troupe. I explained to the worker and the librarian why this might not have been that strange for this era.

The librarian Nanci Young then told me that there was probably information about Smith College’s banjo club in the yearbooks and other student records.

The intrigue meter couldn’t go any higher.

Then, she looked at my table. I had requested forty-one boxes and needed to scan thousands of pages of letters and diaries during the five or six days I was in Northampton after the residency had finished.

“Is that the work you are supposed to be doing?” she asked nicely.

No, it was not.

But I was so intrigued by the idea of being able to do a deep dive into one all-women’s banjo club. When I finished A Most Perilous World, I returned to the Subversive Sisters of Smith College’s Banjo Club.

In That Half-Barbaric Twang, Karen Linn writes about how certain professional male banjo players wanted to elevate the banjo and bring it “into consonance with official Victorian culture,” that wasn’t what happened. If you look at the images and ideas in popular culture, “on a deeper level there was continuity in the society’s idea of the banjo,” which was an instrument associated with Black Americans and rowdiness.

Seeing images of the Smith College Banjo Club in Blackface and high-necked, frilly white Victorian dresses made me want to learn more about them and the cultural moment they were a part of— that’s next time.

Bluegrass is certainly the first thing I’d think of when I saw Victorian ladies in black face holding banjos!